(On Sunday, the New York Times with unwonted liberality published an Op-Ed by Kenneth Wolfe, "Latin Mass Appeal." In the editorial, Wolfe reflects on the liturgical crisis of the last four decades, its origins, and Pope Benedict's support for the Tridentine Mass, which, with his imprimatur, is growing in popularity and visibility. These are my own anecdotal reflections on the New Order in the Church, its cultural implications, and the new signs of vigor that are challenging decades-old attitudes and hegemonies.)

In the foreword to his 1988 Gelebte Kirche: Bernanos (in English, Bernanos: An Ecclesial Existence), Fr. Hans urs von Balthasar wrote, "The flourishing of Catholic literature, which blossomed so splendidly with Bloy, Peguy, Claudel, and Bernanos during the first half of the century, seems to have left no heirs. We often regret this fact. But we have done very little to make our own what we have already been so richly given."

It is unfortunate that von Balthasar's statements should be so self-evidently true. Catholic Christians are ignorant of or alienated from the early 20th century renaissance of Christian thought. This alienation is parallel with a widespread ignorance of the root-and-branch sources of Christian culture. This ignorance is itself part of a wider cultural and historical amnesia, but there are concerted efforts to change this state of affairs. I intend to highlight a few of them.

Lay movements such as Communion and Liberation, the journals Communio, The Chesterton Review, and Second Spring (UK), the new religious orders and institutes such as the Fraternity of St. Peter, Benedict the XVI's pontificate and his freeing of the classical Roman liturgy are all powerful spokes in the wheel of reform: all are working in some measure for lasting renewal, renewal founded on the actual precepts of the Second Vatican Council and its call for resourcement. But what prevented the widespread success of the Council in the first place? Taking a look at the most deleterious after-events of the Council may give us some insight into our current situation and provide prescriptions for future action.

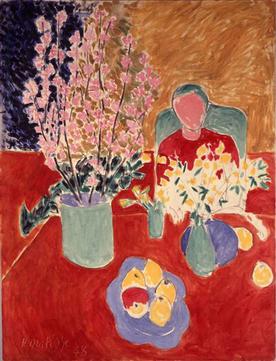

Perhaps the most arresting cultural effect of the bungled implementation of the Council was the rapid destruction of the classic Christian aesthetic: much that was beautiful was callously destroyed or altered, retaining, however, the cheap thrills of devotional kitsch. To my mind, it is not coincidental that the wells of Christian inspiration seemingly dried up at precisely the moment when the Roman Church began to abandon en masse its liturgical and artistic patrimony. In recent decades, we can claim very little of lasting liturgical value: no liturgical art, architecture, or music worthy of its subject matter. But there too we see some incipient dynamism: the University of Notre Dame School of Architecture is establishing itself as a leading institution for church architecture, and the new institutes and orders devoted to the classical liturgy are increasingly in need of new and larger churches to house their growing congregations. In music too, we see the gradual recovery and dissemination of Gregorian chant and Renaissance polyphony. That recovery and creative re-reception is necessary if we're to again have a native school of liturgical composition.

Perhaps the most arresting cultural effect of the bungled implementation of the Council was the rapid destruction of the classic Christian aesthetic: much that was beautiful was callously destroyed or altered, retaining, however, the cheap thrills of devotional kitsch. To my mind, it is not coincidental that the wells of Christian inspiration seemingly dried up at precisely the moment when the Roman Church began to abandon en masse its liturgical and artistic patrimony. In recent decades, we can claim very little of lasting liturgical value: no liturgical art, architecture, or music worthy of its subject matter. But there too we see some incipient dynamism: the University of Notre Dame School of Architecture is establishing itself as a leading institution for church architecture, and the new institutes and orders devoted to the classical liturgy are increasingly in need of new and larger churches to house their growing congregations. In music too, we see the gradual recovery and dissemination of Gregorian chant and Renaissance polyphony. That recovery and creative re-reception is necessary if we're to again have a native school of liturgical composition.

The abandonment and repudiation of the classical liturgical patrimony doubtless did much to dry up inspiration, but the concomitant surrender of the educational and apologetic achievements of the past only exacerbated the crisis. In the early twentieth century, the Church, as Fr. Aidan Nichols put it, was a "presentation of truth, goodness, and beauty that was at once a powerful philosophy, a comprehensive ethic, and a vision of spiritual delight." The abandonment of a coherent and reasoned apologetics (pre-empted doubtless by the many doctrinal controversies that rendered the apologetic task largely moot) and the missed opportunity after the Council to renew and reinvigorate the philosophical life of the Church only weakened the Her appeal to men and women of genius. The parochial clergy, whose self-proclaimed task it was to interpret and implement the Second Vatican Council, seem, in retrospect, to have been willfully ignorant of the best currents of European and American Catholic thought and art: instead of attempting to leaven the minds of their parishioners with the best, they often chose the expedient and shallow, adopting music, theology, and architecture devoid imagination, beauty, and order: they served up theological pabulum and political ideology instead of the thinkers and writers like Henri de Lubac, SJ, Hans Urs von Balthasar, Jean Danielou, SJ, Joseph Ratzinger, and our very own Dorothy Day (whose life and work seems to me to be the most striking evidence for the possibilities of renascence and vigor in the American Church).

That they chose the easy way is not altogether surprising: an immediately fruitful and lasting reception of Vatican Two would have defied conciliar odds (councils are notoriously productive of schisms, heresies, and controversies); immediate optimism should have been disciplined by a strong statement of the challenges at hand.

That they chose the easy way is not altogether surprising: an immediately fruitful and lasting reception of Vatican Two would have defied conciliar odds (councils are notoriously productive of schisms, heresies, and controversies); immediate optimism should have been disciplined by a strong statement of the challenges at hand.

I hope that the efforts at reform, particularly the recovery of the classical liturgy, will spark a renascence of Christian artistry, but suppose that does not come to pass. Previous eras of the Church have been characterized only by stability, not by grandeur or sublimity. Extraordinary outbursts of creativity are fleetingly rare, and men do not live perpetually on the heights. While we hope for the future and the improvement of our estate, we should make every effort to preserve and generously disseminate the patrimony of our past. I believe the pontificate of Pope Benedict will be particularly decisive in this effort.

All of the efforts of the great pre- and post-conciliar thinkers and actors were ordered towards recovering elements of Catholic life they thought had been overlooked or overlaid in the Tridentine Church: recovering the evangelical counsels for the laity and their transforming role in secular society and the indispensable centrality of the liturgy in the life of the Church and of the individual Christian. In short, the Council was indisputably a call to perfection and holiness in life, liturgy, and theology. That's our still task, a task admirably summed- up by Fr. Aidan Nichols, OP: "What the Church can do today is to reform herself by repeating like a mantra the words 'only the best will do': the best intellectually, morally, aesthetically."

The Church must not settle down with what is merely comfortable and serviceable at the parish level; she must arouse the voice of the cosmos and, by glorifying the Creator, elicit the glory of the cosmos itself, making it also glorious, beautiful, habitable, and beloved. Next to the saints, the art which the Church has produced is the only real 'apologia' for her history. . . The Church is to transform, improve, 'humanize' the world --- but how can she do that if at the same time she turns her back on beauty, which is so closely allied to love? For together, beauty and love form the true consolation in this world, bringing it as near as possible to the world of the resurrection. The Church must maintain high standards; she must be a place where beauty can be at home; she must lead the struggle for that 'spiritualization' without which the world becomes the 'first circle of hell'.Joseph Ratzinger, The Feast of Faith, 124-125